I wait for you

Like the desert waits for the sea

Like the pen waits for its ink

Like the flower waits for its nectar

Like the bird waits for its nest

Like the tortoise waits for its shell

Like the child waits for her milk

Like the egg waits for the yolk

Like the thunder waits for its clap

Like the nail waits for the hammer

Like the voice waits for its song…

I wait

Like a breathless, anxious exile,

Lost in unfamiliar presences

Pummelled by strange silences

Wetting my pillow with tears of my blood.

I know you know how I feel

And feel what I feel

And see why I must feel the way I feel

And why I must wait for you

And why, because you’re not here,

I must feel the fever of a maniac

Longing for a touch again

That, like the pebble in the ocean

trapped in the prison of the unknown,

will renew my strength and remake my face

and spring me anew like a fresh proud foliage

breaking out of the wasted branches of a dying tree.

For this I must tell you:

My love for you is the true love of a man for his lover

The untainted love of a woman for her man;

The blood of unwriteable poetry,

Of fire stoked in the hearth of remembrance,

Of blood knots sealed at the shores of distant rivers

Of umbilical cords joined by the past and present

Unfeeling Time will never sever.

Our love is two rivers in the confluence of shared memory,

Dusky rivers that will not now flow backwards,

Rivers that are the mermaid’s songs

Pulling together the hair of friendship,

Diminishing the shadows,

Mending the distances,

Echoing the birth cries,

Like the sound of long cannons.

Waiting (for all who do not wait in vain)

Ewan Alufohai’s The Moto Boy: A Review

In an interview Chris Ugolo and I had, over four decades ago now, with Chief Wale Ogunyemi, one of the greatest actors and dramatists that ever lived in Nigeria, the late Chief and author of the wave-making play, The Divorce, had in his attempt to state the kind of relationship between a medical doctor and a literary artist, declared: “The medical doctor treats (while) we the dramatists entertain”. While this view may have appeared to be giving separate roles to the doctor and the writer, it has become increasing clear that there are doctors who are writers and that no such separate roles, strictly speaking, really exist: the writer is both a doctor and an entertainer, doctor because he not only therapeutically heals the wounds of an increasingly growing band of followers which constitute his audience and the bulk of his readership, but also entertains them. The healing potential of art screams for attention in a nation such as ours in which things are hardly what they seem to be, a nation in which the more you look the less you see; a nation in which the people’s psyches are constantly being battered by failed infrastructure, failed leadership, failed services, failed promises, failed banks, failed dreams and visions, failed economy – in fact, failed everything. This is a nation that has systematically given us less to cheer and hope for even as the drums continue to beat for a moral paradigm shift in seasons where hunchbacks have become endangered species simply because the warped and twisted imagination of ritualists believes they are secret vaults to prosperity when their hunches are used for sacrifice! In a nation that has no place for dreamers, the writer’s choice has been not just to hold a mirror up to the society, but also to point the way forward in its healing, its re-engineering and its rejuvenation, his vision constantly anchored on an irrevocable mantra: hope

We had the interview with Chief Ogunyemi, as I said before, over four decades ago, and as if to affirm the position that no thick lines really exist between the medical doctor and the literary artist, Nigeria continues to parade a bevy of beautiful award-winning medical doctor writers: Dr Wale Okediran, novelist and former President of the Association of Nigerian Authors, Dr. Femi Olugbile, Medical Director of the Lagos State University Teaching Hospital and author of the collection of Short Stories, Lonely Men (Longman, 1987), which won the 1986 Association of Nigerian Authors Prose Fiction Prize, and now, the toast of today, Professor Ewan Alufohai.

Ewan Alufohai, is a Consultant Surgeon, and, in my opinion, one of Nigeria’s best. This is a writer who, as Professor Imobighe says, “besides his surgical knife, lies a surgical pen for dissecting the ills of our contemporary societies and patently providing the precise direction and the available choices open to both the leaders and the led.” (Foreword v). Besides The Moto Boy, he has written a previous novel, Alien to Poverty, and a collection of short stories, His Lordship’s Visitation. In these books, Ewan Alufohai, like a comb strives to rake through the dense foliage of our failures and fears to straighten our values and prune our commonalty. He is a sensitive mirror, refracting our embattled circumstances and showing us the narrow, yet right, path we did not take, are not, and may, perhaps, never have thought of taking, in our quest for self-aggrandizement and blind pursuit of vain glory and lucre.

In The Moto Boy, a novel of twenty-four chapters,Ewan Alufohai largely advances, albeit in a horrifying and scathing manner, the previous themes of failed hopes and blind values. He clinically purviews the dreams and aspirations of a young motor boy who strives to be different from the others who had been before him and to set a new standard for the driving profession in his country. As if to prove that we do not need to first have a name or the wherewithal to bring about positive change of our society, the author deliberately decides to use a lowly hero as solid metaphorical prop. The son of two poor villagers, Jiba has had to abandon his education when his father cannot pay his school fees, and much to the embarrassment and shock of his mother, opts to be a motor boy! Being a motor boy is the last thing Iyajiba would have wished for her son, because she sees it as degrading for her in the polygamous home of competition with other women whose children are in school. But she is soon to yield to him when she sees that he is unrelenting, and finally hands him to his transporter relative, Ademeji, as a motor boy apprentice.

Jiba’s encounters, the speed with which he learns his trade while an apprentice and the revulsion with which he holds the uncanny and reckless irresponsibility of lorry drivers buoyed and incensed by their beliefs in sordid rituals and charms as protection and immunity against road accidents, are critical strands which shapen the story and are instructive to the reader. Jiba distinguishes himself as a motor boy, cutting no corners in his training to be a lorry driver, and in fact goes to the Motor Licensing Office not to bribe the examiners who would be coming to examine him for a Driver’s Licence and certificate, as was the practice, but in fact to request that the examiners examine him thoroughly so that he would be appropriately tested and ready for the world. Jiba, from this encounter, proves to be one who seeks to be an asset to the driving profession and not a liability to other road users. It is, therefore, not surprising that when he passes his test in flying colours, he is further to prove, to the amazement of all his peers, that you do not need to use charms as a driver to avoid accidents. Rather, certain principles must be obeyed: respect for the high way code, regular maintenance of your vehicle and proper focus as a driver. On the part of government, primary attention must be given to road maintenance, because most accidents are caused by bad roads, even when the driver on his part obeys all traffic regulations and maintains his vehicle.

That Jiba becomes a standard bearer for the driving profession and the toast of all is not surprising, because at the very early stage, he knew what he wanted and where he was headed. He looked the strange one, because he refused to do what others did and instead wanted to be different. That he vehemently refuses to be lured into using the so-called ‘protective charms’ after his ‘freedom’ as a motor boy in a world in which the belief is strong that with those charms one would have an accident-free career is bolstered by his early experience of an accident involving Kabiru who was an ardent user of charms. Why didn’t the charms stop Kabiru from having the accident? And so Jiba risks the anger and wrath of his close relatives in insisting that he did not need charms. We are glad that Ewan Alufohai’s novel leads us to the eventual triumph, not disgrace, of Jiba and celebrates his victory over the forces of superstition and retrogression. The national award that Jiba receives at the end of the novel is a salutary affirmation of the relevance of his campaigns for road safety in Nigeria.

It needs be stated that The Moto Boy, an easy-to-read novel, narrated from the third person point of view, is the author’s modest contribution to the campaign for bringing about safety to our roads. The author is concerned that far too many lives are being lost through the carelessness of drivers, particularly those who believe in the use of charms and think that nothing will ever happen to them, even if their vehicles do not deserve to be on the road. As Alufohai himself says: “The interest in road traffic accidents is especially a big issue in medical practice, and for the surgeon, the interest is more heightened as he invariably deals with victims of road traffic accident hence any contribution to minimize the calamity is worthwhile.” (Preface ix). It is noteworthy that Alufohai clearly deconstructs his interest and pain by dedicating The Moto Boy to the legendary Nigerian writer, Chinua Achebe, who was maimed in a road traffic accident and is living the rest of his life on a wheel chair, and to the memory of the wife of his “dear friend, colleague and classmate, (Mrs. Anne Isekwe) who was mortally injured in another accident while giving a helping hand to victims of road traffic accident.” (Dedication iii).

In all The Moto Boy is a worthwhile read and a mighty contribution to the plethora of battles for sanity on our roads. I believe very strongly that you would be making your own contribution to ensure that this battle is won by picking up for yourself, your friend and family, The Moto Boy.

Title of Book: The Moto Boy

Author: Ewan Alufohai

Publisher: Safmos Publishers, Ibadan

Date of Publication 2009

Pages: 217

I Come Home Again

I will come home again. Your door will open to me. Your open arms will welcome me. Tears of joy in your eyes, you will make me feel as if I had been gone for many, many years – not just 365 days. You will make me know how much you had missed me, and, still filled with the joy of my return, you will take my hand and lead me excitedly to our familiar table opposite which Baba sits, and there we will try to fill the gaps created by our absence from each other, and our heads robust with memory, talk and talk and talk. We will talk and never tire. We will talk late into the night and into the morning hours.

We will talk about the family, our land, our hopeless people and our even more hopeless and clueless leaders. We will talk about the unending power failure, the growing unemployment, the anger in the land, the rising arrogance in the brood of looters who have turned power into self-aggrandizement. We will talk about how many of our street people have been kidnapped with huge ransoms placed on their heads for choosing to live in a nation without security. For small talk, we will talk about the baker’s wife who eloped with a trailer driver, because her man was no longer a ‘man’; Atine’s sister who killed herself as she tried to abort a six month feotus implanted in her by a boyfriend she soon found was not a movie actor as he claimed, but a man who did drugs at the Murtala Muhammed Airport and occasionally hurled empty monologues at the skies…

We will talk and talk of the many many things you hinted me in your e-mails while I worked in the fever of my blood Up There. And I will elaborate on my own hints I sent you in text messages at the breaking of the news, details of which you got to read yourself from the papers and watch on television: the new rage of mindless people in our land who, for reasons that still confound, bomb churches, schools, public places, police stations and barracks, killing hundreds and maiming hundreds more, raising a pall over our land now increasingly being littered with a mass of graves…

And now, I have truly come home, and when I open the door, there are no arms to welcome me, no tears to make me feel I had really been away for too long. The driveway is empty; just as the car park where your Nissan used to sit. There is no laughter in the compound, let alone someone to take my hand and lead me excitedly to the table where we would unloosen our hearts in talk. The room is empty. The table is gone, like the chair that faces it, where Baba used to sit. No bird tweets a welcome, and taking a walk down the corridor that adjoins Baba’s room, there is the silence and the emptiness of a graveyard. I open the door to his room: the emptiness yells at me. No one is there to greet me.

Baba is gone…

Baba is gone. And with it, everything seems to be gone too: the laughter, the talks, the welcomes… The mood of my nation has changed too. More despair seizes the streets; more bombs detonate, and we remain at a loss as to the meaning of all this. 365 days appear to have become an eternity! The road is filled with cow dung and littered with human faeces. I decipher a path laid with landmines and broken bottles, at the end of which is a tattered green and white flag hanging limp like the Baker’s manhood on a lonely post. Further down is a new road, swept clean by the vision of the restorers at whose beautiful entrance is the sign: THE FRUIT OF WORK.

And I make this pledge, with God on my side, that my voice will not grow weary of song, nor will my feet be tired of dance, for I know that just as He who created the pencil also created the eraser, He raised everyone of us to be minesweepers… My hope is untrammelled like the hope of a child for the milk of its healthy, happy mother. By His grace, my shadow will lengthen above the eaves and my strides, longer now, will shame the cheetah in the bush tracks of the savannah. I will work the talk and talk the walk. Eyes forward, I will remain a part of the re-awakening, and the walk for the reshaping of my land, never, never giving up.

I will follow my Mind (A Tribute to Reading)

I will follow my mind like the dance that follows the song like the river that runs its course like the fire that burns and burns I will follow my mind like the tender bird that wakes up at dawn to sing of the plenitude of harvest and the certitude of rain I will burn the midnight oil to last till the morning hours a voyager on a quest for the true meaning of life I will search the vast oceans ruffle the feathers of mountains seeking words in silent plains giving names to nameless babes I will touch the lonely trees make them breathe and dance again scan the magical horizons firming the bricks of dreams for my new house of words I will follow my mind till dreams cease to die till I light the flame and open the doors of beautiful gardens where wisdom grows of cavernous rooms where knowledge opens its arms like a happy loving mother urging her child to come on and be smothered. I will follow my mind to where victory stands tall like a strong soldier and the storehouse of abundance flows like an endless river. I will follow my mind till I strengthen my voice till I build myself into a castle that will never fall.

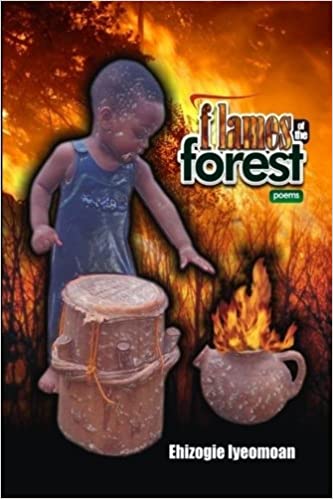

A Few Words on ‘Zogie Iyeomoan’s Flames of the Forest (Poems)

I will be quick to let you know that ‘Zogie Iyeomoan, by way of self-introduction, describes himself in this elegant collection of poems as “an unrepentant lover of African literature and history”. He also makes quite a few poetic “confessions” and “claims”, but more on these shortly.I have no reason to doubt his claim to being “an unrepentant lover of African literature”, having before now encountered his poetry on social media and seen the passion with which he goes on creating, on a near daily basis, poem after poem that can conceivably be described as of high quality.

If I have been struck by the kinetic energy that suffuses his ‘social media’ poems, the dexterity with which he unreels the tapestry of his poetic imagination, I have also not failed to wish that these poems and his many others lying in quietude in memory cards and flash drives are “transmogrified” into some “permanence” in the nature of a book. Now in this homogenous form, it could either be transmitted into other forms – electronic/digital, etc. – or left as it is.

If I have been taken in by the sensitivity with which he articulates his perspectives and the depth of his love for words, I have also been impressed by his relishing of a broad-based collocational geography in amplifying and contextualizing his messages. All these, put together, have given his poetry an unforgetability – a certain kind of haunting presence – which at last this volume not only validates but consolidates – to my great joy, and relief!

Flames of the Forest, then, is an effort that reveals the flaming innards of a young Nigerian writer’s passion for the beaded word and a more than passionate affirmation of his love for literature, especially the poetry genre. It showcases his joy, pain, surprise, disappointment, frustration with his country, his continent, its past, present and future. It is a roller-coaster of emotions and that this intense presence is urged on by the solidity of the panoramic sweep of the 76 poems is remarkable indeed.

In one of the poems, Yeomoan declares: “I’m not a renowned poet/just an apprentice”. Going further, he states: “If I be a poet/let my words give life”. Much as these “confessional”, profoundly self-effacing lines may suggest that in his youth and innocence the poet may not even be sure of who he is, a close reading of this collection reveals that itis certainly not a journey of innocence. It is, in fact, the foraging of a vibrant, multi-talented writer in the panoply of experience seeking to forge a defiant, personal poetic mode; the relentless, undefeated and undefeating effort to create forest fires.

Flames of the Forest, in my estimation,is a powerful collection that demands the attention of all who seek not only beauty in poetry, but also the poetry of beauty. But beyond this, is the undiluted truth it unleashes, damning the consequences.

‘A Variegated Tapestry:’ A Review of A.R. Yesufu’s Visions and Recollections (Poems)

In his preface to the collection, Visions and Recollections, the author notes as follows: “I have allowed all shades of ideas and facts to jostle for a place in the variegated tapestry of my mind” (xi). He then appeals: “… I hope that readers would equally be sympathetic to accept and allow the potpourri room to flourish.” (xi).

I must confess that this rather self-effacing and subtle appeal to the reader’s understanding far from being an apologia clearly underscores the profundity and immutability of the poetic innocence which informs the thematic concerns of the volume. No doubt, the close relationship between a poet and his internal and external landscapes often accounts for the deep panoramic sweep and shifting kaleidoscopes we find. For A.R. Yesufu this holds quite true, and forcefully too, because here is a poet who is imbued with a very alert consciousness and is therefore quite sensitive to his universe and the landscapes which shape it, on the one hand, and the inner world which cognize, validate and accentuate his unique artistic vision, on the other. Although he accepts the Keatsean axiom of the poet being the “most unpoetical of anything in existence” and, therefore takes consolation in the “catholic consciousness” of being a receptacle for “both internal and external impressions”, it is noteworthy that the clearly defining characteristic of Yesufu’s poetic tour de force lies in the deftness with which he navigates and mediates this duality.

I am of the opinion that the poet asking for the reader’s understanding is, perhaps, overindulging. The Nigerian literary landscape is littered with all sorts of writers, some of whom ornately assert themselves as ‘poets’. But rather than claiming to be a poet, with all the potential he is imbued with, Yesufu chooses to describe himself instead as ‘poetic’, and this even with some hesitance! Just as our own Wole Soyinka asserted some time ago, albeit in a different context, that a tiger will do better to pounce rather than just making proclamations about its tigritude, Yesufu has chosen to write without ascribing any tag to himself. His reason is remarkable: he doubts if there is “such a character who is born a poet” (vii). I disagree with him here. Some poets are born, and his Visions and Recollections affirms he is one of them! If you cannot talk about the song without the sound, can the ‘poetic’, which arises as a by-product of a profound artistic imagination, be divorced from the one who creates it?

I hold it as a demonstrable fact that A.R. Yesufu’s Visions and Recollections, though an annunciation. is an affirmation of the writer’s passion for poetry and also marks a definitive trajectory of a private poet with a unique and fecund imaginative, cosmopolitan and public consciousness. Operating from a wide thematic canvass and a broad-based and extraordinary lexico-semantic range, it is a collection that enthralls and excites in the variegated tapestry of its spread and in its stylistic rejuvenation. Thus, I make bold to surmise that what the reluctance to be called a poet may have achieved is not to diminish the quality of Yesufu’s versification but, sadly enough, to attenuate his prolificacy. Nevertheless, we are exceedingly glad that though he is no longer here with us in the flesh, he has left us with visionary and recollective nuggets which time and space shall never tarnish and the triumph of which death can never sound a knell.

Visions and Recollections is a collection of fifty poems some of which were created on the spur of the moment, “in spontaneity”, as the poet says and under “more stringent deliberation”, (vii) i.e. with emotions being “recollected in tranquility” at a later date, to borrow those memorable words of Coleridge. The collection spans three decades and in it, the poet confesses to allowing, as we noted earlier, “all shades of ideas and facts to jostle for a place” in his mind. It is, therefore, not surprising that the poet works within a stylistic spectrum, some poems not easily rendering their meaning and requiring the adroitness and perceptibility of a locksmith, and others teasing the hermetic masquerade in their seductive and alluring simplicity.

The volume opens with a captivating poem entitled ‘The Year’s End (1997)’ in which the poet showcases his ability to deploy figurative expressions to capture his vision of a dying year. He states: “The year trudges towards the last bend/ On the road to its transient decease/ Heavily loaded/ Knock-kneed/ Back bent by knapsacks of memories” (1.) His capacity to describe objects and phenomena in a captivating manner also shows in ‘The Full Moon’ when he writes: “Now she’s ripe/ The moon is ripe/ Well-rounded by Fecund Time/ Like a plump pumpkin” (3).

I find the poet’s description of Benin City in the poem, ‘Benin City – a Bird’s View’ (43) one of the most picturesque in the collection as he writes: “Benin City/ Ubinu, Igodomigodo/ Edo n’evbo Oba/ Ochre-red city of blood/ moat-engirdled bosom/ Confluence of ancient and modern/ Where the musty and the glossy/ Like two master wrestlers/ Are locked in a perennial duel” (43). He waxes most philosophical in the poem, ‘The Riddle of the Road’, where he states: “The road is life spread out before the wayfarer/ Its spring-sprout is a breath/ And its winter whimper a breathless ebb/ Life is a road to an end that’s endless/ Crucial choices are roads taken and not taken” (45). He goes further to assert: “The road is a tragic cord/ Tethering the womb to the tomb” (45).

No doubt, Visions and Recollections is a beautiful poetry collection by a poet of great insight, a man of few words, a teacher and mentor, an erudite scholar who was as humble as he was noble, an outstanding talent, a voracious and consummate reader … As the blurb writer graphically captures him, he is “a poet of changeable moods” and in Visions and Recollections, he is “simultaneously the benign satirist, the philosopher, the dreamer and the love poet with an exceptional capacity to evoke both visual and auditory responses. His lyricism moves from the real to the unreal impressions, which assume concretion through vivid and exact expression of details.”

I recommend this volume to all who not only seek the naked and immutable beauty of truth, but the quintessential and exalting truth of beauty.

Title of Book: Visions and Recollections

Author: Abdul R. Yesufu

Publisher: Deaconry Press Limited

Date of Publication 2016

Pages: 95

Price: Not Stated

24.07.18.

A Review of Charles Omoifo’s Please Remember Me (Poems)

Charles Omoifo’s Please Remember Me is a book of poetry dedicated to the “memory of those who died so that a Nation can grow” (dedication page). This dedication at once points to the direction of the author’s concerns: the sacrifice for nationhood.

The author does not specifically mention this nation (in his dedication, at least), but we are not fooled. He is talking about our own dear country, Nigeria; its losses, its labyrinthine struggle; the murky waters in which its rulers swim as they hold blood-stained hands over those they are supposed to lead; the vision of its youths who are continually repressed and suppressed; the rape of the polity and, above all, the possibility of hope. The tonalities are redolent and strident. As Professor Sam Ukala who writes the foreword for this volume states, the volume is “…absolutely uncompromising as it holds up a mirror to us all, showing to which side of history we shall belong”.

Omoifo’s portraiture refracts a nation state which Ukala again describes as “the front line of a running battle between freedom of speech and the brutal denial of it.” As he goes on to observe “Those who stay on the side of freedom of speech and protest ineptitude and injustice easily get killed by ‘the cruelty’ of the ‘country’s Establishment’, ably represented by trigger-happy law enforcers”. (But Omoifo does not hurl his ideas at us like empty slogans; rather he devises vital stylistic props to project his unique artistic vision).

Please Remember Me derives its title from ‘Colonial Legacy’, the last poem in the collection in which Ayemere the son of Ubiaza, declares an intention to return to the campus after the holidays, working in the farm. As we glean in the poet-persona’s narration, the sentence constitutes the last words rendered by the young man whose dreams held the key to a bright future:

We worked till the sun was high; we rested

In the farm hut. His eyes were with me

But his inner eye was far away. Then he said,

Brother, I am going to Campus day after

Tomorrow. Whatever happens, please remember me. (187)Ayemere’s words are loaded, born out of a certain foreboding and fear that he would lose his life, and that he would not return. He loses his life and does not return, as the brutality of the Establishment is unleashed on the metaphorical Campus and death tolls its worrisome and dreadful bell.

It is certainly the desire to celebrate then, that propels the kinetic energy behind the tapestry of Omoifo’s narration. But Please Remember Me is more than just a tribute. It is a profound acclamation of the zest, beauty, variety, vivacity, virility and undying potency of African oral culture. The volume displays the author’s irrevocable attraction to the lores of his people, the Esan people, and he weaves this attraction into a mosaic of patterns that brings back memories. As we get continually sucked into an alien techno-culture and the power of DVDs makes us spin, Please Remember Me urges us to remember the very things that weaned us; that we grew up in; that defined our existence; that gave us values; that made us both human and humane. In other words, it urges us to remember the village square and the moonlit nights, not the artificial gardens and meretricious street lights that now rule our lives. It is an urge, a call, a strident call to a past of glory.

That Omoifo is able to reflect, to a considerable extent, the dramatic possibilities of oral culture even in the medium of cold print is at once a clear indication of his alertness as a poet on the one hand, and his skillfulness as a raconteur on the other. Moving from an oral/aural medium to a written and, if you like, ‘deaf’ medium remains one of the stiffest challenges facing the African writer till date. But while some of them have tried to get around it by transliteration, others have tried to retain the immediacy of speech in cold print and maintaining the dramatic effects of the oral medium in the written medium. Omoifo goes beyond just creating an interface style; he uses the English language as a standard, but he sustains the rhetorical qualities that define African speech. The following extract from ‘Ikhio Dance’, the eighth poem (or do we say, ‘Narration’) in the collection speaks volumes:

When mother was going to the market Oliza

Marcelina said, leave the load for me Oliza

Then mother took load light, saying meet me up Oliza

But Marcelina settled the load on a child’s head Oliza

Has her head become too delicate to carry load? Oliza

(30)That he means this poem, like other poems in the volume, to be performed rather than recited is very obvious, and he therefore sees speech as not an end, but a means to reinforcing the dramatic possibilities of his poems. He subsumes the poems to be mere script, mere potential action, while the actual performance remains the very essence.

Please Remember Me certainly rings with the clarity of a gong. The 47 poems it parades, despite their variegated nature, are all united in the affirmation of the poet’s rare gifts; they proclaim a poet who not only sees, but also hears. While some of the poems may be said to give their themes away so easily, because of their high suggestiveness, others are crisp and proverbial, relying on the poet’s vast and enviable array of allusions and references. To say that Omoifo’s lexico-semantic geography is broad is an understatement knowing full well that, apart from the references he makes to his oral (unwritten) culture, he is a well trained agriculturalist. The plethora of agricultural jargon that pervades the texts encapsulates the depth Omoifo owes to his professional calling.

In all, Please Remember Me is a mighty great contribution to African poetry and an affirmation of the resilience of the human spirit.

Book Sub-title: Narration on the Murder of Ayemere Azemheobor

Publisher: Idehuan Classic Books, Nigeria

Date of Publication 1999

Pages: 187

Price: Not Stated

Review: The Return of Ameze

Because of the close relationship it shares with life, literature has often been seen by critics and those who value it as life itself. Here, life is not just the mirror into which literature looks and which it refracts, but the one which constitutes all of its essence.

The essence of literature as the wellspring of our survival as a people also points in the direction of the complexion of the present and the future, even as it is the memory of the world. Lying within the lexico-semantic geography of memory is the fact that literature never forgets. In the hands of a visionary creator and a skilled craftsman, it is a good reminder. It is in the mould of literature as a reminder that I would like to cast Felix N. Ogoanah’s The Return of Ameze, a novel which, in my humble opinion, has the potential of stamping its authority on the Nigerian literary landscape sooner than later. This is not only because of the quality of the novel’s topicality, but also the sheer virtuoso and pathos with which events in the novel are woven. I should note at this point that while many artists have often sacrificed art in pursuit of topicality, a great many have adroitly executed compelling craftsmanship in their handling of events in their society. They have deployed considerable stylistic tour de force and shown a penchant for harmonizing the what with the how. Ogoanah belongs to this latter group. I must say that I am overwhelmed not only by the quality of the novel’s call for restraint in our pursuit of lucre, but also by the manner it fragments linearity to project a vision that is at once suspenseful and gripping.

Ogoanah’s The Return of Ameze is a novel which deals with the disturbing issue of women trafficking to Europe for prostitution purposes. But much more than anything else, it focuses on the horrific and intense psychological and moral subjection that women are put through in the process. It is the need to project this psychological and moral subjection that informs the shifting kaleidoscope of his narrative vision. He creates a young woman by name Ameze who has big dreams of a wonderful future like every young person out there and vows to remain a virgin until she is married. Against a backcloth of poverty, disease and squalor, Ameze lives her dreams, falls in love with a young graduate called Frank who vows he would marry no other person but her. But because dreams, like roses, do die under the elephant grass, people and events conspire against her and she is soon forced against her wish to go to Europe, precisely Italy, to become the breadwinner of her family, made up of her ailing father, her mother and her two sisters. Told by the heavy society woman, sponsor and trafficker, Madam Vee, that her daughter is going to do decent work in Italy to lift the family out of poverty, Ameze’s father, Okoro, is too blind to read between the lines. But even if he reads through, he is too consumed by the fact that other people’s children had gone abroad and taken their families out of poverty to allow Ameze marry the man she loves. Madam Vee takes on every responsibility of sponsoring Ameze to Italy because she is convinced that Ameze’s beauty is worth putting huge stakes on.

When Ameze arrives in Italy, she finds out that she had not been brought to do the decent work that had been promised her and other girls, but to prostitute. Unlike other girls, she refuses to cooperate with the men Madam Vee brings to her for sex. She goes through a tortuous process when she is gang raped by three men under the watchful eyes of a camera and under Madam Vee’s heavy sedation. The picture Ogoanah paints of this episode is telling and full of pathos:

Ameze woke up, violated, blood every where, as she groaned in pain. She couldn’t understand what had happened to her. As she cried for pain, it seemed she bled for all the maidens in her clan. She thought about her sisters. She tried to call on the gods she knew, but they were too far away to answer. She was alone in the world, as she watched her dreams drift away. The experience was more than losing her hymen. All she stood for was gone – her entire family had been violated! The dignity and the noble ideal she lived for and wanted to pass on to posterity had been violated, desecrated in a foreign land. She felt unclean.

‘They have taken it!’ She cried. ‘Nothing is left. I’m not different from the girl in the street!’ (243)

Ameze’s self-pity is worsened when she realizes that she can neither go back to her inviolate state nor could she have the means to return to her country. It is these reasons and the fact that she still needs to salvage her family from intense poverty that eventually break her will and make her surrender. The next few years see Ameze in the sex trade, remitting thousands of dollars home to her parents. Her father builds a mansion, sends to the best school in the city, her two sisters who had hitherto stopped schooling because he couldn’t pay their school fees. He also buys a fleet of cars, takes a chieftaincy title and joins a secret cult. In no distant time, he had become one of the most prominent men in the state, dining with, and befriending, the high and mighty. His voice is heard in high places and his opinion is sought on issues that matter. No one remembers that he had been a poor carpenter who could hardly afford three square meals a day, let alone take care of his health and send his children to school.

But while her family situation in Nigeria improves by the day, Ameze’s deteriorates, because of the physical nature of her job. In no distant time, she has caught the dreaded virus that has no cure, and she is brought to her father’s house to die, a tragic victim. The contrasts Ogoanah paints of Ameze’s going and her return are quite stark and basic. When she was leaving the shores of Nigeria, she had been hale and hearty, strong, talented and beautiful – a woman of every man’s dream. When she returns, her body is like whittled sticks, and she is a few hours away from her death.

But beyond the physical return of Ameze is a return of deeper spiritual significance. This return comes about a few moments after she physically gives up the ghost. Ameze acquires new strength with which she subjects those who had caused her early death to the worst torture imaginable. This torture is both psychological and physical for the victims, and we see Ogoanah unleashing the instrument of poetic justice.

Bolstered by the suspicion that Ameze’s death must have been caused by someone, Okoro goes to consult a witch doctor named Ogizo,who advises him to look at his mirror when he gets home, that whoever he sees there is Ameze’s killer. Ogoanah narrates as follows:

Five minutes, ten, thirty… nobody was there apart from his own image. He stood, waiting and trembling. He wasn’t sure who would appear. ‘Whoever it is must die. I hope… I hope it is not any of my daughters’, he thought and prayed. ‘What about Maria? Well, I don’t know’. He had been in the room for nearly an hour. ‘Ogizo never lied. What is happening? Where is the killer. Ameze’s heartless killer?’ He began to yell. ‘Whoever you are that killed Ameze, my daughter, show yourself now in the mirror and let me see!’ There was no response apart from the echo of his voice. After waiting for over one hour, he thought he saw an image behind his own; the dark shadow of a woman. He cleaned his eyes with the back of his palm and stared harder. The image did whatever he did. (293 –294)

While this scene may be laughable, it is serious and ironical enough, for Okoro soon finds that he and no one else sent Ameze to her early grave by the pressure he and his family had put on her. When he prepares to leave the room, having seen no one else in the mirror but himself, he confronts the hand-pointing figure of Ameze at the door, and no incantation can ward it off! This figure would haunt the entire family for hours and doors and windows would, on their own accord, begin to open and close, forcing the family to take the decision that the house that had been built on Ameze’s blood and sweat is haunted. They are forced to relocate somewhere. Did Ameze have her revenge? Largely, she does, because the author tells us that even Madam Vee goes mad in the end, tortured by her and the murdered Uncle Nikky, the owner of the NGO, which had been vigorously campaigning against female trafficking.

The Return of Ameze is more than just a statement; it is also a warning to those who trample on innocence and violate virtue; a warning to heartless human traffickers who, in the pursuit of material gains, court violence and wreck the dignity of African womanhood; a warning to those who see nothing good in humane values and must plunder the very essence upon which we stand as a people and a nation. In its seething condemnation of the dishonest and irrational ways in which people seek material wealth and power and die after the things of the West, Ogoanah flagellates those who must make others slaves for them to be free. His attack spares no one: the traffickers and those who benefit from trafficking directly or indirectly; the perpetrators of the Machiavellian principle of the end justifies the means even when the end is not in sight; those who have thrown morality and conscience overboard in their personal greed; agents of government who, rather than attack the problem of female trafficking headlong, develop logorrhoea and engage in empty rhetoric that is full of sound and fury, yet signifies nothing. It is pleasing indeed that rather than prophesy the tragic end of all evildoers, Ogoanah shows that end coming to pass. We see much of this in the two incidents earlier referred to: the forceful relocation of the Okoro family and Madam Vee’s madness. We are impressed by his appreciation of the capacity of the wronged to seek vengeance, whether dead or alive.

Ogoanah’s narrative style in The Return of Ameze is quite intricate, though it is easy to assume that the omniscient perspective gives him sufficient room to indulge the reader. As suggested earlier, the author weaves his tale like a spider weaves his web, creating labyrinthine patterns, which often gleam like a mirror in the sun. But the narrative is deliberately fragmented, with episodes from the past brought in at intervals even while the narrative thrusts itself forward and the reader is left breathless. Much of the suspense the novel achieves is derived from this stylistic feature. Just as a nation’s history is in her geography and her geography is in her history, Ogoanah’s story’s beginning is its ending and he largely positively exploits the psychology of the reader for the full stylistic benefits of the novel.

It is also remarkable that Ogoanah deploys what comes very close to an interface style in his manipulation of the language of his characters. Although coming from a different linguistic background from the characters who speak in the novel, he has achieved considerable approximation in their linguistic nuances. The annotations he offers of certain words from his characters’ linguistic repertoire are quite helpful to the reader encountering the cultural background of the novel for the very first time.

Altogether, The Return of Ameze is a simple tale told mightily. It is a disturbing and haunting tale indeed, which, like the reality that gave it birth, is most deserving of our attention. It is my hope that those who read this novel would not only see something personal to take away with them, but would also have the larger conviction that with a paradigm shift, the nightmare of female trafficking which has for almost two decades been the lot of this nation would one day die a silent death.

Title of Book: The Return of Ameze

Author: Felix N. Ogoanah

Publisher: Evans Brothers (Nigeria Publishers) Limited

Date of Publication 2007

Pages: 301

Price: Not Stated

The Snake

At your creation, He put a lamb in your heart and enjoined you: ‘Dear Child, go into the world and be gentle and meek like the lamb’. But when He was away on just a moment’s respite (for even the Creator must have respite from His work), the devil, walking Creation’s Garden, chanced upon your innocent being on the first lap of your journey to the world.Because you were still pliable (like clay), the devil seized your heart and put a snake in there, pushing you down the conveyor belt quickly, lest the Almighty returned from His respite to see the corruption of His work. The devil enjoined you as you went: ‘Dear Child, go into the world and do evil!’

These thoughts made Ganiyu grit his teeth. Those days of cruel admonitions, those days when they suffered the torture of Ismaila Buka’s wit and acid remarks! Those days when they were stretched out on their backs like cow-hides, held by the huge muscular hands of their bigger pupil colleagues and received the alligator-pepper-fevered violence of Ismaila Buka’s koboko (which Buka said could chase out the most obstinate of devils) and the spittle-spraying chorus of his angry voice as the horse-whip descended in quick, maniacal, sensation-dulling succession, like a koranic recitation gone berserk.

Ah, to remember those days at the koranic school!

It took Ganiyu quite a long while to pick himself up from the small heap he had formed at the worst part of the dirt road. The grime clung to his danshiki and so did the smell of rotting flesh, for he had landed on the very top of a sacrificial offering (three potsherds) bearing the entrails of an animal he could not identify, and a soot-covered calabash that contained some dark-blue concoction and parrot feathers that exuded an infernal stench whose origin he did not know and would probably never know. He felt humiliated, and even in this humiliation, he could see the children of the street, mirthful with laughter, break into a run, scattering, like exploding rubber seeds, in different directions. The anger came upon him then with the fury of a whirlwind, encompassing his small bulk and shaking him with such a violence that he felt himself being lifted clear off the ground, so that he unconsciously flailed his hands. The veins in his neck stood out and his brain grew hot like molten lava. He would kill these children if he laid his hands on them; he would kill them and no one would ask him questions. Allah!

The fact that he would not be able to identify the real culprits who had brought him this shame did not matter. The children belonged to the street; they were all children of the devil (for was that not what Ismaila Buka used to say of stubborn children?) and he would treat them like a mass. He would spare none of them, for any punishment one of them suffered was the punishment of all of them. And the punishment of all of them was the punishment of the whole street, of its useless, wicked inhabitants – its men and women who begot the children and who stood or sat in mirthful groups around the verandahs, tittering and making music out of his humiliation. He spat. Allah! The whole street has witnessed my fall!

His left knee hurt badly and, as he bent in the half-light to examine it, he could feel the sharp, spine-tingling painful sensation. I bruised it in my fall. It was on the knee that I first landed. Bending lower still, in spite of the pain, he took in the full weight of his injury. There was a deep gash where his skin used to be, and now it oozed blood and was covered by the earth and grime. He tried to walk, but found he could only do that with some effort – by putting a great deal of his weight on the right leg for the time being.

I will have to limp to work, a moving pit latrine.

The thought of the pit latrine made his entrails revolt suddenly, and he felt like vomiting. But he held himself back with incredibly great effort.

I will have to get a sonsorobia. But I wonder if that will kill this smell on me which is like that of a five-day old corpse. It’s like I have died.

And now, he was like the typical cripple who, suddenly getting back the use of his legs, was beginning to walk anew. It was painful and odd, but he had to make use of his leg. He had no choice.

When I get to the chemist’s yonder, I will buy red-and-yellow capsules. This leg hurts like death.

As he limped down the street, he could breathe in deeply the air of merriment. It was as if a small celebration had, at his own very expense, began on the street verandahs. The radiograms blared Christmas carols and the sharp sound of firecrackers and knockouts rang out in the humming, deepening, dust-laden night air.

They must be celebrating my fall. Not just the approaching Christmas.

At this point, it was difficult for him not to play, in his mind, the whole nightmarish experience – his fall, his humiliation, his despair. He saw it slither into his path from the corner of his mind, which in fact was the shrub that flanked the road. It moved with an evil that was real and true in the half-light. It was no make-believe snake (it did not look like one) and his heart had leapt with his fear. To step on it; to step on a live mamba! His reflexes were sharp, even as he shook in horror. Next thing he knew, he was flinging himself backwards and rolling over many times, wrestling with a fear that was macabre and a panic that was palpable.

I knew nothing for a while even as I lay still. Until the laughter came like the cacophony of exploding rubber pods. And I saw the many forms of the children – wraiths and millipedes – emerge from the bushes, breaking into a run, and then disappearing into the belly of the on-rushing dusk, into plantation gardens, half-completed and completed buildings that dot this over-crowded street of evil. And the mothers and fathers on the verandahs… Then I knew…

Why would the children choose to play such an expensive game on Old Ganiyu?

They want to laugh at my expense. Because it is Christmas season and they have money to buy rubber snakes.

He wished he had known. He would have reached for the toy and the string its owners had used in manipulating it across the road, snake-fashion. With the ‘snake’ and the string, he would have sprung at the urchins who crouched (he could understand now) somewhere in the undergrowth, not very far from him, waiting. He would have strangled them and made everyone realise that pulling jokes on Old Ganiyu had its limits. Allah, I wish I had known! But I will have my own back!

The next day saw Ganiyu walking down the street on his way to work, looking as sombre as a pall bearer, though his senses were as alert as a cockroach’s. As he looked out for the familiar, suspicious gathering of children, he suddenly began to sweat, in spite of the harmattan haze. Of course it would be futile looking for the particular children who had contrived his humiliation the day before, as children filled the street, flying kites, building sandcastles and caterwauling. But he was confident that his chance would come.

He limped slowly down the street (because he still felt pain on his left knee, although he had, on his own accord, treated it with the red-and-yellow capsules and the cotton wool he had bought from the chemist’s shop). He fingered the string of the catapult he had neatly concealed inside the pocket of his danshiki and his excitement grew. It was a small catapult, but Kinuko who had recommended it to him after listening to his tale of humiliation called it ‘Big Pepper’. Kinuko was a fellow night watchman at the Bexton Supermarket who had fought in the Civil War and who said the ‘Big Pepper’ was one indispensable demobilising weapon that came in handy, in spite of the sophisticated military arsenals at the disposal of the soldiers, during the war. That he was the unacknowledged hero of the war, Kinuko always wanted everyone to accept, and his voice always bore the mark of his pain, apart from its crushing lucidity and humour, whenever he revealed that he sold his manhood to the war. (People who listened to him often wondered what he meant, especially when they knew that he came out of the war complete with his vital organs).

“You never know,” he would defend his infertility. “It could be shell-shock. “You need to see what I saw during the war. Machine guns booming and mortars falling…”

Like Ganiyu, Kinuko had no children, though, unlike Ganiyu, he had a wife. But Old Ganiyu had nothing to blame on the war. His had been the ordinary life of an ordinary man and he had lived it as quietly as he could. When the crisis broke out, he had tried enlisting in the army in Kano, but he was not accepted because of his hunchback. As a field soldier, that is. But he was valuable as a cook, and the man who did the menial jobs for the field soldiers. His constant regret was the action he had to miss in the front down South. As a child, he had played soldier with his mates, and his one dream had been to lead a Jihad to fight and unite the people of his country for Allah. He refused to get married, because he thought he saw fulfilment in being alone. “I am a hunchback, anyway… who wants a hunchback?”

The children probably suspect me, thought Ganiyu now as he fiddled with the catapult. Kinuko’s instructions were very clear in his mind. He had to keep an eye on the children. You never know, after what happened yesterday, they may be up to new tricks. “Be on the alert. Your aggression may not necessarily be loudly provoked. What you seek is revenge and any child you see who appears capable of mischief is good target. Select the grittiest pebble, aim neatly at the little godforsaken devil and pull the string. Then hurry down the street as if nothing had happened and let the child enjoy the sheer violence of the punishment.”

Were the children clairvoyant? Did they know his intention? Did they know he carried a sinister catapult? After every humiliation he suffered in their hands (and he had suffered many) Ganiyu had always walked down the same street with no vengeance in his heart. And the children had remained in collected groups, confident and within his reach; and had even had the effrontery to try new tricks on him. But now that he was ‘armed’, they did not come anywhere close to him.

They know, they know! He could not, however, say exactly how they could have known.

Maybe it’s their guardian angels. Evil things! But I’m not fooled. I’ll continue to pass this street. It’s the only street I take to work and I’ll continue to be on my guard.

Old Ganiyu took the catapult with him every day he went to work, and like the other day nothing happened: no children played any new tricks on him. The children went about their business, not appearing to even notice him.

Maybe they’ve decided to leave me alone for good, he thought. Now, I’ll go down the street in peace. He even began to think that he was probably over reacting; that, maybe, he could make them Old Ganiyu’s friends. They’ll call me Old Man, Hunchback, but I’d laugh at them and they’d be tired. They’d plant plastic snakes on my path and I’ll kick the things and laugh and they’d know I’m no fool. I’d admonish them (not beat them like Ismaila Buka used to beat us at the Koranic school in those days) and I’d tell them not to play pranks on Old Ganiyu. They’d stop putting plastic snakes on my path in the half-light, or hurling stones and banana peels at me. I’ve walked down this street for months and the children ought to be my friends. I ought to be one with the street.

But a painful smile creased his face the moment he reached this point in his thinking. Haba, children will always be children. They’ll always be evil!

The rainy season soon came, and with the violence rainy seasons are known to come with in the city – tempestuous storms and regular flooding. Ganiyu hated the evenings when it was raining and he had to go to work. Ozolua Street was sure to be in flood as it became the reservoir into which the water, debris and muck of the city emptied themselves. A tunnel led to the moat and it had been constructed with millions of naira to combat the regular flooding. But it had been blocked for years with the muck and corruption of the city, and nobody seemed to care. The flood period was the season the children of Ozolua Street loved most. It was the season when the bowels of the tenements opened and they, tiny snakes, wriggled out to gambol and caterwaul in the brownish water.

The water in Ozolua Street was always knee-deep in the flood season, and, when the rains were heavy and regular, the level often rose beyond that and beyond, too, the small fortresses of hurriedly constructed walls in front of the verandahs of the houses to keep water from the rooms. And then the rooms would become water, with the water rising to bed level (and sometimes above it) and making lightweight objects float. Because of the flood situation in Ozolua Street, a mischievous journalist in his gossip column had spoken of his longing for a day that the government would turn the flood site into a giant-size swimming pool where the state’s athletes appearing for the next Olympic games would be trained!

Ganiyu always took his umbrella along. With rolled sokoto, he would make his way through the street, avoiding as much as possible, the deep gorges and ditches that lay their snares before the unwary traveller. A walking stick came in handy. In spite of his hatred for the rains (and the flood), he always felt an upwelling of the spirit. The humiliation he had suffered seemed a distant memory. The scars seemed to have healed; the pains seemed to have gone. Only the beauty of flame trees what he knew. It was moments like this that his mind would wander nostalgically to his childhood, to fifty-five or so years ago when he grew up in the backstreets of Kano with his two brothers whom he last saw when they were going to enlist in the Nigerian Army in Kano, and they ate tuwo and suya. Ah, those were restless days in spite of the power of the Religion, and Teacher Ismaila Buka of the painful koboko! Life was lived in complete abandonment, but, no, they did not play pranks on older people. The Religion forbade that. We did not plant plastic snakes on the paths of travellers to scare them. The Prophet would not have liked that.

Ah, he was so prepared to die for the Religion in those days! Yes, those days before the bombs began to drop, before the war began and brothers began to kill brothers. And what purpose was there in all that? Was war not supposed to be fought for the Almighty and not man? It was senseless killing. It was plain genocide. And he had blamed the Almighty for the senselessness of it all; its sheer meaningless and lack of logic. Could the Almighty not have intervened? Could He not have brought the people under His command, His power, and used them for the glory of His honour? Or was it deliberate? Was it the Almighty’s design? He realised that not much had changed since the war ended and decided that it could not have been His war. Why could it be when the rich were still amassing wealth and growing richer by the day while the poor still suffered the yoke of poverty and oppression? When you look back at that war, those who died were the poor, the poor ones like my brothers whose loss killed my poor parents…Those who benefited were the rich ones, who became even richer…

Other thoughts grew like bacteria in his mind. He allowed them incubate and fester. The Almighty’s will is sometimes strange, he thought. The Almighty moves in mysterious ways. For some odd reason, he found himself smiling. It was the inscrutable smile of a mask.

One day, Ganiyu went to work. It was the dying days of the flood season. The grasses had grown beautiful and lush like the hair of a mermaid, having made the most of the regular rains. Ganiyu was humming a tune by Dan Maraya Jos as he walked down Ozolua Street. He felt light-headed; good. The children were about their own business, playing, mindless of him. Throughout the flood season, they had been about their business, but he was sure as he knew he was Ganiyu that now that the rains were disappearing they’d soon forget the joys of floodwater and turn their attention on him. He did not trust the children. He never would.

So, when he came across the long object that lay mysterious, motionless, across his path in the half-light, his instincts had become alert with intimations and the joy of knowing. Children would always be children, he had always thought, and here he was now being proved right. Did he not say they would never give up? That they would continue to play pranks on him? But he would not fall for it like the other time, he resolved. No, NEVER!

As he watched the object, Ganiyu could imagine the children in the undergrowth, waiting breathlessly (like the other time) for the right moment to begin to pull the string, to begin to manipulate the object, snake-fashion, across the road to the other side where they lay. He could feel their laughter and the laughter of the whole street waiting to explode like seedpods in the harmattan. Old Ganiyu is no fool any more! He scoffed at the imaginary children. He has grown wise.

Two thoughts crossed his mind: to pick up the object, or to gallantly walk over it and continue as if he had not noticed it at all. But he preferred the former. Why, it was better to hold the rubber snake in his hands and let the children know that he was Old Ganiyu, and he was not afraid anymore. It was better to let them know that he had mastered their tricks. Why, he could even take the snake to work and show it to Kinuko, or even present it to him as compensation for his ingenious suggestion of the ‘Big Pepper’ which he had had no cause to put to use in the long run.

When he came very close to the long object, he expected it to move, for that was how the other one had moved calculatedly the other time. But it remained immobile. He had the urge to pick it, but he resisted it. Better to touch it, touch it like a real man. When he touched it, it felt cold and slippery and his spine tingled with the electric sensation. So like a snake. So life-like.

Then he bent lower and took the object in his hands.

Ganiyu would never know how it happened. One moment, he was holding the object and the other the object was wriggling out of his hand and he was falling backwards with a frightened scream. The meaning of what had happened did not take too long to register. Ganiyu knew snakes well enough to know that the one that had just escaped from his hand was not a plastic one. He knew the sensation well enough to appreciate the fact that he had been bitten. He could not see it in the half-light, but the sharp pain was there all right in the finger where the two fangs had gone in. And then the gift of knowing turned to the interminable fear of dying and the fear of dying took the sharp edge of a profound horror. A mamba, a king-size mamba! Kai!

He did not quite know what to do. He was confusedly torn between reaching for the wound with his mouth to suck out the poison, running down the street to the chemist’s shop for help, and howling like a blind maniac.

And when the wave of soul-churning nausea began, he swooned. His breathing came in gasps. The sweat poured like rain.

I know nothing about this, oh Mighty One. I know nothing. His lungs were on fire. He clutched at his chest. The swooning had intensified. He was like one in a nightmare.

So I am going to die!

The thought struck him with the force of a lightning bolt. Its effect was so devastating that he swayed, tripped and fell. He lay in the dust of the galloping dusk. Nothing about him moved, except the wind, and the grasses which had grown lush and fresh like the hair of a mermaid in the flood season. Oh Mighty One, help me. Save me!

He managed up with tremendous effort, staggered. It was strange the way he felt. Am I really going to die. From snake bite! He could hear voices. He could see the small crowd that had begun to form around him, the same way a partially blind man could. He peered. He saw children. Children. More children. He was beginning to lose total grip. He felt tiny arms on him. “Sorry… sorry…sorry”. Solicitous voices. Sympathetic voices. But a deep voice rang out clear in the midst of these tiny near, yet so faraway voices, totally drowning them, “Leave him alone, or do you want trouble?”

“He needs help”, the children’s voices chorused, defiant. “Don’t you see that he is in bad shape?”

Old Ganiyu was muttering: “Snake. Snake. I’ve been bitten by a snake”. He was still muttering this even as he lost total grip and he felt his legs giving way. Many tiny hands formed the soft pillow upon which he fell, as he still muttered, “Snake… snake”.

“Let’s carry him to the chemist’s,” the children’s voices came up. “To Ladejo”.

It was like the tiny string that held him to consciousness snapped suddenly and Ganiyu found himself in a long, dark corridor that belonged to the present, yet looked like yesterday. He felt the corridor embrace him in such fierce grip that he opened his mouth for a loud scream. No sound came out. The corridor appeared to widen before his vision. He gave a deep sigh, everything about him went totally blank. Then he knew no more…

Three Hundred and Sixty-Five Days After (For My Father, Pa Wilfred Amadin Adagbonyin, 1936 – 2011)

Memories of you are etched in stone, like your admonitions and your dreams for your children. Today, you die again, and the freshness of it all shames the eternities that these long days and nights conjure.

A brief phone call from your last born, my brother, who cuddled you at the back of the car moments before on the feverish rush for the hospital, and the tone is set for the heart splitting news that would crash our world like a pack of cards. Unfettered wailing is the answer I get from my call back, and the message is clear: Baba is gone! The white shroud drapes the body of our patriarch, and the journey to the morgue is only a second away! I crush the silence in anguished gasps, and the black pall is all I see…

It’s all playing back again, Baba – the unreeling tapestry, and the kaleidoscope of meanings.

Long meetings into long and fetid nights; unending journeys and detours; convolutions of untiring dread as we beat quiet tremors on the road to a plain never visited for 29 years… This is the plain of my birth and your birth – our root, my beginnings, the plain where, like you, I was first washed in grains of sand and powdered with the dust after my first birth cry – the reward for my mother’s groans in parturition unsilenced by the irrevocable resilience of the cooing birth attendant, and your prayerful watchfulness unbroken by the distance of several towns away…

The house still stands, manned by a now near-maniacal, reprisal-harassed, bemused, usurping denizen and a temperate young uncle. It still stands on a plain I knew as a child -stolid and defiant, a part of it in ruins… The pear tree, its wings cropped, gives a loyal, amputated salute to the unseen stranger, and the pond where the ducks used to frolic with the snorting pigs is now but an imagination. An eerie silence pervades the plain that would soon echo the bad news we have brought…

How can a land be so full of men whose every gaze portends evil? Men without ears. Men who do not grow weary from drink. Men who have lost their teeth even when old age is still thousands of miles away. Broken men and haunted women who see in your coming an answer to the previous succulent, and now peeving, promises made by thieving politicians and lying technocrats. I see children with balloon bellies rich with kwashiorkor, and lean-framed youths with hungry eyes, evaporated stamina and famished hopes. I see women with babies strapped to their backs, and several children more in tow, their height belying the fact that they were only just a few months apart…

We will have our way; we will not be beaten by the wily ways of wizened illiterate relatives we cannot even recognize, relatives who never looked up our father when he was alive, but now claim to know him better than we the children and charged you an arm and a leg just to give our patriarch the Christian burial he deserves… We will not give our arm or our leg, but the leg and the arm of a cow we shall give. We shall expiate your greed with resolves of steel rolled on conveyor belts bearing mounds of pounded yam, egusi soup and cow leg and gallons of palm wine and cans and bottles of drink…May you give your arm and your leg to unknown spirits in your frolic!

We broke not our vow. These mounds of earth are the visible chapters of our sojourn, the final testaments. And so you lie today victorious six feet beneath the ground, your dreams unbroken, your promises fulfilled, your joy boundless, your hopes high, your face wreathed in your trade mark smiles that could melt the stoniest of hearts. These are the plinths of our joy, the bastion of our resilience, the monoliths of our own victory.

You will not die a second time…